"We'd set up a dozen crows when this red tail came from behind our blind and grabbed a decoy. The hawk took it down to the ground and mantled over it," Jack Wood recalled, describing a hawk's stance over its prey. "The hawk was there for a good five minutes before it realized the crow was wood. I guess it was a compliment to my carving."

A retired police detective from Trenton, Jack first began carving in the '70s. Today much of his work depicts waterfowl such as the wood ducks and greenwing teals found along the Delaware River and its environs. A wood duck drake, a carving that balances artistic interpretation with realism, won Best in Class at the 2005 Tuckerton Decoy Show in Tuckerton, New Jersey.

To understand the art of decoy carving, one must understand its utilitarian origins. North American decoys have a long history; Eskimos used wooden fish to lure other fish within striking distance of handheld spears. Other native Americans made reed ducks to draw prey towards nets. (The word decoy apparently comes from the Dutch word de kooi or duck.) The first European settlers might well have adopted native ways, although later use of decoys was not consistent. Market hunters, arriving in droves in the mid-19th century, did not have to rely so extensively on decoys to hunt waterfowl. With their increasingly sophisticated firearms, hunters decimated the massive flocks that congregated around the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River. The Migratory Bird Treaty of 1918 put an end to commercial hunting, but by then the waterfowl had grown scarce - and cautious. Sportsmen turned to elaborate and realistic decoys to bring the ducks in.

Gradually, carving evolved to an art form widely considered unique to North America, morphing from gunners' birds to decorative slicks (also called smoothies), the highly painted birds that grace many homes. Considered by many to be a form of folk art, decoys have, nonetheless, grown increasingly sophisticated - as have their collectors. Events featuring decoys draw large crowds. The Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art, in Ocean City, Maryland, hosts its annual carving championship each April. which attracts almost 1,000 carvers and 6,000 visitors. Past competition categories have included decorative, lifesize, miniature, interpretive, contemporary, contemporary antique, gunning class, etc. But purists argue that the best decoys exist at the juncture of function and form. The mark of a master carver can be found in a decoy that simultaneously pleases the eye and fools Mother Nature.

In the northeast, distinct schools of carving developed in different regions. The sportsmen of Chesapeake Bay, hunting waterfowl that congregate in large numbers, shot over large "rafts", or groupings of decoys. Geese, after all, land among geese. In the interest of time, carvers spent less effort on intricate carvings and instead painted on the feathers.

Delaware River sportsmen sought ducks - diving ducks, such as buffleheads and mergansers, and puddle (or marsh) ducks such as mallards, teals, pintails and wood ducks. With fewer decoys to carve, the artisans spent more time shaping the birds, carving out tail feathers and adding texture to the wood.

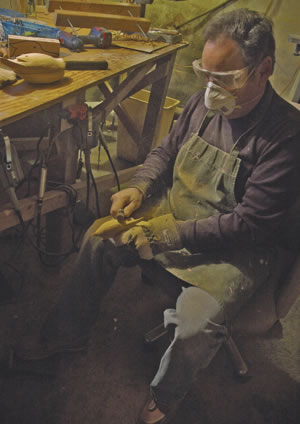

In his shop, Jack Wood begins work on a merganser, drawing the basic outline of the bird's body on two blocks of Maine Cedar. (The cedar, which is buoyant and carves easily, must be dry and preferably knot free.)

Jack cuts the wood into the rough outline of merganser. With a drill press, he bores holes through blocks. The holes are temporary, pegged with dowels to hold the blocks together while he shapes the body. After cutting top down with a band saw, he then shapes the side view. He follows the same procedure to carve the head, which is made of tupelo, cutting top down and checking for balance.

"I don't use old hand tools, like the old-timers," he explains. "They would use just knives, a hatchet, a drawer knife and a rasp, whittling things down A rotary grinder makes the process a lot shorter. It's kind of hard to work with but I've been doing it for years. If you're not careful you can take too much wood off and once you take too much wood off," he adds with a rueful laugh, "you've wrecked it."

Eventually the body, now beginning to resemble a duck, goes into a vise. Jack uses a drawknife to peel the wood off the decoy's sides.

"This is a pretty fast process but you have to be careful. There's an imaginary line in the middle here, where the grain runs. If you go too far it rips big hunks off. If you do it in the right spot it comes off evenly."

The wood curls and falls from the merganser's body. Peeling wood off the block is roughly comparable to carving hard cheese with a dull knife. The smell of cedar rises up from the basement floor. Chips accumulate quickly as Jack works the surface of the decoy. "There are many phases that don't go so fast. Carving the head and getting the eye in takes time."

Experience guides the best carvers. The decoys reflect the artisans' familiarity with birds from their years of handling ducks. Inexperience shows.

"The problem for a lot of carvers is the decoys are too square, and that's the kiss of death for decoys," Jack explains. "Many guys who are really good decoy carvers make beautiful decoys but they're square. When I get this the way I want it I take a wood shaver and begin to round the bird. Now if you look at this you can see where it's starting to get a round look."

The merganser takes shape, but there is still much work to do. The decoy must be clamped down and hollowed out, a process not unlike preparing spaghetti squash. Symmetry matters. Uneven sides cause the "birds" to float off center in the water. Carvers go through a process of trial and error to get the balance, working with variables such as the weight of the wood and the amount hollowed out. The decoy must, if knocked sideways in the water, right itself. It must be glued together, the dowel holes sealed with food filler, and passed through the drum sander. The primaries (the more noticeable wing feathers) must be carved out. Then the head must be cut out.

Jack determines where the cheek and the eye channel will go, and moves to the sander. It is a remarkable thing, to watch a carver work by eye. "I've been doing this for thirty years," Jack says. "You make a lot of mistakes when you're learning. It takes a long time to get to the point where you have confidence and you just rip through it." Many carvers hunt, although perhaps an equal number work from stuffed birds. The hunters claim to produce the most accurate decoys, arguing that taxidermists have a tendency to overstuff the birds and distort their size.

A dowl and strong glue keep the merganser's head attached to its body. Head positions vary depending on the carver. Some "birds" carry their heads high. Others seem to sleep, their bills tucked into their feathers. The merganser holds its head at a jaunty angle, as if surveying its surroundings with a lively curiosity.

The decoy must still ride the water correctly. Carvers balance the "birds" by attaching weights to their bellies. The ballast helps balance the decoys and causes them to displace the same amount of water as a real bird. Different decoys require different weights; Jack produces his own by pouring lead into a mold. The weights must be somewhat heavier than the wood; if the decoy flips over the ballast will help right it. (Marsh hunters sometimes toss decoys from their boats.) Plastic decoys have entered the marketplace, but not all hunters have embraced the substitute. To keep their decoys from disappearing downstream, hunters anchor them with tether lines.

Then the decoys are ready for painting. Jack applies an oil-based primer and lets the bird sit for twenty-four hours. The decoy must be sanded until its surface is smooth. To capture the gleam of a duck's feathers, Jack mixes irridiscent powders with the paint. "It took me years to get this right. If you do too much it looks fake."

Jack shows off a male wood duck, resplendent in breeding plumage. It is hard to imagine launching a piece of art into a marsh, perhaps to be blasted by errant shells. Many decoys, in fact, go on to galleries, where collectors pay princely sums for the best pairs. The wood duck will find a roost, at least before it is sold, at Decoys and Wildlife Gallery in Frenchtown, New Jersey.

Novice collectors might find the aesthetics of the best decoys difficult to define. Nonetheless, the best work strikes a common chord.

"85% of our visitors will pick birds by the top 5 carvers," says Ron Kolbi, of Decoys and Wildlife. "We don't use the best birds to hunt. They're too difficult to produce. It's hard to find good carvers who do it all. Too many guys can carve but they cant paint."

At Mr. Kolbi's gallery the decoys, almost literally, fly from the shelves. Typically delivered in male-female pairs, they decorate a long wood shelf that travels the length of the gallery: pintails, mergansers, mallards, woodies, gadwalls, teals, black ducks, and others. The collection turns over regularly, its finest examples luring buyers the way the best decoys lure wild birds.