New Jersey Route 10 races west across the Morris County townships of East Hanover, Hanover, Morris Plains, Denville, and Randolph until it ends at its intersection with U.S. Route 46 in Roxbury Township. Seeming to ignore the county's long and illustrious past, the highway slices through age-old communities replete with historic properties, testaments to heart and soul that is difficult to imagine from the commercial clamor of modern traffic. At the highway's end, just off the old, now-vanished, Ledgewood Circle, a stone's throw from the mall, the Drakesville Historic Park pays tribute to Morris County's pedigree of innovative pioneers.

Ledgewood's historic district consists of three museums located on Main Street —the King Store, flanked by the King Homestead and the Silas Riggs House—all in the vicinity of the Morris Canal's Inclined Plane 2 and 3 East and two canal basins. To explain how the buildings and historic features relate to each other and to their era, rigorously researched accounts have been prepared by Ruthann Seraly for the Register of Historic Places, and by historic consultant Dennis Bertland for a subsequent Historic Structures Report. Various narratives are readily available on the Roxbury Township website and in the on-line editions of The Drakesville Times. To quickly understand where the names come from and how they fit together, here is a very condensed version distilled from those resources.

European settlers first came to the New Jersey Highlands for opportunities afforded by hills rich with iron, as well as vast forests for fuel, and plenty of water to provide power to process the ore. Roxbury, which was incorporated as the fourth Morris County township in 1740, was no exception, and initially stretched from Lake Hopatcong south through Chester. There was soon a small settlement along the road that ran northwest from Morristown to Newton, originally the Lenape Minisink trail across the state. Abraham Drake arrived there in 1751, constructing and running a mill, then a tavern. One of his grandsons, Jacob, operated the tavern, and later achieved prominence as Colonel of the western battalion of the Morris County militia during the Revolutionary War, and as a member of the first New Jersey Legislature. By 1783, Jacob owned nearly 900 acres in Roxbury, and had married Esther Dickerson King, the widow of George King, who was the son of another early settler, Constant King. Their home still stands at 6-8 Emmans Road in what would become known as Drakesville (present-day Ledgewood).

In 1801, the New Jersey Legislature chartered the Essex-Morris-Sussex Turnpike, the first of more than one hundred 19th century thoroughfares across the state, and which incorporated the existing road through Drakesville. In combination with the Dover turnpike, built west from Rockaway to Flanders in 1812, the new junction spurred commerce in the hamlet. By that time Silas Riggs, a tanner who planned to provide leather pouches for transporting iron ore, had moved over from Mendham. And, also from Mendham, Dr. Ebenezer Woodruff, who married Jacob Drake's oldest daughter, Clarissa. Woodruff's younger brother, Absalom, soon followed and married Drake's youngest daughter, Eliza. Jacob and his sons continued to operate the tavern, along with two mills and a store.

When Colonel Drake died in 1823, his tavern had closed. Many of Morris County's iron forges and furnaces had shut down for lack of charcoal fuel and cheap transportation to markets. But one year earlier, while fishing on Lake Hopatcong, George McCulloch had a revelation: a way to build a canal that would transport goods, including coal for iron furnaces, from the Delaware River to Jersey City. McCulloch's idea—to use a series of locks and a new innovation, the inclined plane, to haul boats—760 feet up from Phillipsburg to Hopatcong, then back down 914 feet to tidewater at Newark Bay—inspired sufficient investors to begin work on the Morris Canal in 1825 along a route surveyed right through Drakesville, crossing land owned by, among others, Mr. Young, Septimus King, Ebenezer Woodruff, George K. Drake and Silas Riggs.

Silas "Captain" Riggs took advantage of his position at proposed Canal Lock 1 East and Inclined Plane 3 East, where he excavated the first canal section and eventually owned three canal boats. In 1826, George Drake sold .82 acres along the turnpike to Absalom Woodruff and his partner, Obadiah Crane, who quickly erected a store at this location, directly across from the canal basin site. The store, acquired c.1847 by Silas Rigg's son, Albert, would serve turnpike travelers, canal traffic and the local community for one hundred years.

Theodore King was born on a farm about three miles west of Drakesville in 1843, but spent his first years in Morristown where his father, Thomas, served as county sheriff. Thomas returned his family to the farm where they prospered in agriculture and the lumber business, and his son learned merchandising. Theodore married Albert Riggs' daughter, Emma, in 1873 and took over his father-in-law's store, moving into the second floor of what is now the King Store Museum.

Of all the characters in the Drakesville story, Theodore King is by far the most luminous, profoundly shaping the local economy with extensive ventures at Lake Hopatcong, even as commercial canal traffic declined in Drakesville. He invested in mining, real estate, and hotels in nearby Landing, founded a steamboat company as the lake began to court tourists, and cultivated a massive ice-cutting operation.

Emma Louise King was born in 1881 three years after the Kings had moved into their large new Victorian home next to the store. Her father operated the store, wintering in St, Petersberg, Florida until his death in 1928, at which point his daughter locked the door, sealing the contents in remembrance of him. She hired Miss Paterson to care for her mother, who died in 1935. Then "Lady Lou" and "Miss Pat" lived on the rest of their lives between New Jersey and Florida, Louise conducting her business and hosting weekly card games with the neighbors when home in Ledgewood. She passed away in 1975.

Eight years later the Roxbury Rotary Club enlisted assistance from the New Jersey Conservation Foundation to use Green Acres funding to acquire the Morris Canal Inclined Plane 2 East property and the King site for Roxbury Township. Ten years on, Rotarians had cleared the plane, installed signs, and initiated restoration of important canal artifacts. In 1989 the Rotary turned their attention to the sadly dilapidated King Store, beginning work to clear vegetation and rehabilitate the building, a project that would last until 2000. The Roxbury Historic Trust was formed to manage the Museums at the Store and the King House next door, creating interpretive plans, writing grants, and hiring professional consultants.

"The thing about the King Store is that it is a time capsule," explains John Bolt, a historic architect who works on this and many other historic preservation projects in New Jersey. "The building was locked up since the 1920s. There is a patina of age, an atmosphere that you just can't replicate. Unless it's preserved and interpreted properly, it's lost. This is a unique example. It's not like some of these historic homes where you ask 'well, what do you do with it?'. This story is so clear, and if it's interpreted right people will walk in and say 'wow, look at that'. It's amazing how they did things back then before electricity, how they managed."

On the occasion of Roxbury's bicentennial (after Louise King had passed away) ten-year-old Beth Wack asked if she could photograph the King Store interior for a school project. Her father, Russ, tagged along and made a series of photographs that became an invaluable record for future interpretation. Documenting what the store had looked like fifty years before, the pictures have served as a helpful guide in presenting the store "as it was" in 1928. Visitors walk into an authentic 1920's general store, stocked with original merchandise that includes everything from tools and flour to remedies and sewing supplies; even Japanese beetle traps! One corner served as the Post Office, another stretch of countertop as the district polling place. A 1924 calendar that advertises Anson Ball, a Dover eyesight specialist, hangs on a wall. Another sign pitches milk and cream from the local Kenvil Dairy. In the back room there is a gauge that reached down into the self-measuring oil tank in the basement, cabinet drawers stuffed full of nails and bolts, and a massive icebox built into the exterior wall, its coolant no doubt supplied by King's Mountain Ice Company to keep perishables fresh.

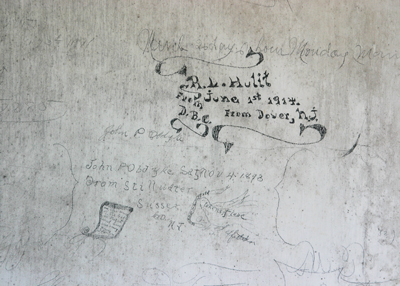

Also left untouched are Theodore and Emma King's second-floor living quarters. The penciled graffiti on the walls yields clues that a fraternity or secret society held meetings high above Ledgewood's Main Street. A spacious attic held ample supplies of grains, seeds and other dry goods that were hoisted up and down by a huge, still operational wooden wheel with hand forged iron rope guides.

Although there are vintage photographs of the site, accurate representation of the complete historic landscape around the store is more difficult to reconstruct. Initial phases of archeological survey have revealed the remains of an outside platform scale, barn and shed foundations, gardens and landscape plants and evidence of early underground water and electrical systems. There are plans to restore the shed that extended off the back of the store. And, with the help of a generous donation from Bruce and Lillian Venner in honor of Tom Venner, the Trust is installing a restored Moline wagon scale, similar to the original Howe scale that stood at the front corner of the store, measuring loads up to five tons, certified by a weigh master using a balance beam that worked much like a doctor's scale. Similar in design but much larger scales were employed to weigh payloads on boats along the Canal.

Soon after Theodore King moved his family into their new residence next door, he began to upgrade the store, which was originally built with rubble stone mortared in three-foot-thick walls. King dressed up the exterior with a smooth coat of cream painted stucco that was scored to resemble squared stone work. The faux joints were painted brown, along with the trim and the distinctive quoins at the building's corners.

A recently-completed extensive materials and finishes analysis of the structure's exterior has revealed the likely presence of Portland cement in the stucco. Why is this a big deal? Although Portland had been invented in Britain in the 1820s, it was not available in the United States until 1868, when David O. Saylor commenced production in Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley. It was not commonly used until the early twentieth century. If the Portland cement is indeed part of the The Portland Cement in King Store stucco appears to be a pioneering example of its use at that time and place, one so rural as Drakesville. Then again, Theodore King's sophistication, and access to world wide markets afforded by Morris Canal boats were extraordinary.

After the Roxbury Rotary turned over the keys of the store to the Historic Trust, they moved next door to the King's sorely neglected home where they stabilized the house, installed electric and phone service, repaired the chimney and raised money for a new furnace. Habitable once again, visitors can roam the grand old Victorian, through the parlor to Mr. King's corner office, or to rooms containing rotating exhibits that explore the heritage that we share with that proud family. And another mystery on the walls, an elegant mural of English countryside decorates the dining room, painted by James William Marland. This English artist, who had property in Budd Lake, was hired by Emma Louise King in 1935 to redecorate her home, The quality of Marland's work in the dining room, and on the upstairs master bedroom and bath stenciled friezes, suggests an artist of some celebrity. But little more than the fact that he sailed from Preston, England, in 1918 and returned there to die in 1972, is known about Miss King's decorator.

Funding for The Roxbury Historic Trust projects at the King Homestead Museums has been provided by the Township of Roxbury, Morris County Historic Preservation, Morris County Heritage Commission, New Jersey Historic Trust, and New Jersey Historical Commission. The Roxbury Township Historical Society owns and operates the colonial Silas Riggs "Saltbox" House, moved from its original location to 213 Main Street to save it from demolition in 1963. The museums are open for tours on the second Sunday of the months of April thru December, from 1-4pm. The annual Living History Day occurs in mid-October. For more information click or 973/927-7603, .

For information on this and other historic sites throughout Morris County, contact the Morris County Tourism Bureau at 973/631-5151 or visit their website.

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Paths of green, fields of gold!

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.

The Millstone Scenic Byway includes eight historic districts along the D&R Canal, an oasis of preserved land, outdoor recreation areas in southern Somerset County

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.