Winter encampments were the necessary acknowledgments of rest and repair that eighteenth century armies gave to the harsher weather and energy requirements of the season. In the American Revolution, the astonishing hardship at Valley Forge, in 1777-78, and two years later at Morristown, during the worst winter of the century (1779-80), are memorialized for the Continental Army's heroic endurance, and the mere fact that the soldiers lived to fight another day. The winter of 1778-79, known as the Second Encampment at Middlebrook, is remembered for the transformation of the American regulars into the disciplined fighting force required to defeat the larger and more well financed British army of occupation.

The American troops emerged from misery at Valley Forge with a crucial alliance with France, and the services of a Prussian veteran, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, whom Washington appointed Inspector General in order to develop a structured military training program. By May, von Steuben had introduced manuals, prescribed drills, and organized a formal Grand Parade to celebrate the French alliance. In June, the rebels won a critical victory at the Battle of Monmouth, and by year's end the army was at an impasse with the British, who were forced to divert much of their force, and quarter the remainder in Manhattan and Staten Island for the winter.

General Washington was obliged to again keep his army in the field in order to hinder British plundering in the New Jersey countryside. By December, infantry began to return to Middlebrook (there was a previous encampment in June of 1777), at the base of the "first" Watchung Mountain. Middlebrook, as it was known, is the name given to the tributary that runs from the Watchung hills down through the gorge at Chimney Rock above contemporary Bound Brook. The artillery, under the command of General George Henry Knox, diverted to a less vulnerable location several miles northwest along the ridge near the village of Pluckemin. Not only was the location more protected, the local thoroughfares—precursors to the present-day state highways 202 and 206, and interstates 287 and 78—were able to sustain the heavy military traffic foreseen at America's first military academy.

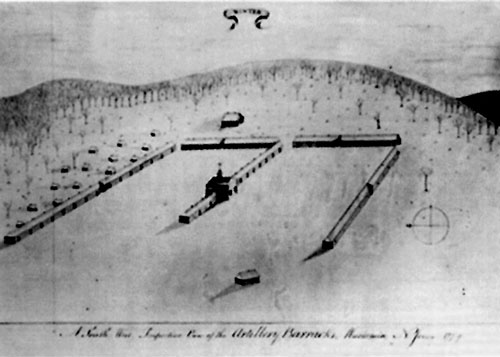

The Pluckemin Cantonment, which was considerably more ambitious than previous efforts, included an array of carpenters, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, gunsmiths and weapons specialists, along with one thousand soldiers who made up twenty-two companies of artillery. In a matter of weeks, substantial structures rose in an "E" formation that stretched five hundred feet, encircling spacious parade grounds along a hillside between the North Branch of the Raritan River and the village. At the center stood an academy, thirty feet wide by fifty feet long, with plastered interior and glass windows, where officers studied and artillerists trained. A headquarters building and a line of barracks flanked the academy to complete the middle line of the "E" sloping downhill. Across the top were officers' barracks and workshops where craftsmen made and repaired equipment. Lining the north edge were more artillery barracks, and on the opposite side, warehouses to store materials gathered to resupply the Continental Army. Quarters for senior officers stood above the formation near the top of the hill, and guardhouses and cannon lined the bottom.

Documents strongly suggest that General Knox, along with his wife and their young daughter, resided at a small Dutch frame-style farmhouse, built in 1772, just west of the Raritan River. It was Jacobus Vanderveer, Jr., son of a wealthy Dutch miller, who lent his home to Washington's brilliant military commander and future United States Secretary of War. Knox occupied the house through the summer of 1779, when Washington decided to move his primary camp north to Morristown. Although the cantonment saw continued use as a hospital during the following winter, the Pluckemin site was abandoned in favor of the Continental Army outpost at West Point, NY, for eventual development as a permanent military academy.

Except for a few acres preserved as a park by the Washington Camp Ground Association on Middlebrook Road in Bridgewater, much of the larger encampment lies buried under Routes 22 and 287. Were it not for the vigilance and brilliant efforts of a local special education teacher and Revolutionary War reenactor, Cliff Sekel, we may have completely forgotten that the Pluckemin Artillery Cantonment ever existed. Certainly, any possibility of excavation and historical evaluation would have been obliterated by the rapidly expanding residential development at The Hills.

In a 2002 Star Ledger newspaper article, writer Steve Chambers described Sekel's contribution:

This legacy was on the way to being forgotten back in the 1960s when Sekel stumbled across mention of it while doing graduate work on Pluckemin at the National Archives in Washington. Locals had always known about the ‘encampment.' Grant B. Schley, who purchased the mountain around the turn of the nineteenth century, had a dream of a resort with a Revolutionary War theme. The federal government considered it for a national park when it was establishing the Morristown National Historical Park in the 1930s. But detailed information about the size of the school and its role in the war were hard to find when Sekel went searching. Frustrated that so little was known about such a tantalizing site, the graduate student switched his thesis and went to work. In the summer of 1966, armed with a machete, he began hacking his way up and down the mountain looking for foundations. The search went on for twenty weeks over two summer vacations. Eventually, a reporter provided a crucial clue. Poring over the archives of her Bernardsville News, Anne O'Brien found a report based on some archaeological rummaging conducted at the behest of Schley. The report noted that a garbage dump had been uncovered that contained thousands of clam and oyster shells. Sekel had been over the pile before, mistaking it for a Lenape Indian pit. Now, reading the photocopied newspaper article in his home in Somerville, he leapt up and raced back to the mountain. Locating the dump, he began clearing the surrounding area, and soon he had found the outlines of a building. It was fall 1967.

It took Sekel another ten years to raise enough interest to secure the site for the non-profit Pluckemin Archaeological Project, supported by the Hills Development Corporation, Bedminster Township, and scores of small businesses, foundations, and individuals. A decade-long excavation, led by Rutgers archaeologist, John Seidel, and a team of volunteers, was guided by a drawing of the cantonment by a Continental Army Captain, John Lillie. Lines of stone and old walls confirmed Lillie's depiction, and hundreds of thousands of artifacts told a fascinating story. Among the most prized were musket balls, a rusty bayonet, and a belt buckle decorated with a canon and thirteen-star flag, the earliest war-time artifact showing the American flag. Monmouth University archaeologist, Dr. Rich Veit, who later worked with Dr. Seidel to reanalyze the extraordinary collection of artifacts unearthed at the site it "one of the great overlooked stories of the American Revolution. The collection provides an unparalleled glimpse of the lives of Revolutionary War soldiers."

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment. Following its occupation by the Knoxes, the home underwent a series of alterations and remained in the Vanderveer family until it was purchased at auction, in 1875, by Henry Ludlow. The house was subsequently owned by the Ballantine and Schley Families, who utilized the property for hunting and polo. In 1989, the neglected and decaying building and property were purchased by Bedminster Township, with the help of Green Acres funding. The house was listed in 1995 on the National and New Jersey Registers of Historic Places, and, in 1998, the volunteer Friends of the Jacobus Vanderveer House came together, resolved to restore, develop and operate the house as a nationally significant historic site and museum. Over the past fifteen years, the Friends have restored the house, created historically accurate period room exhibitions, established historic collections, supported important research, and embarked on a program of education and interpretation to tell the stories, not only of General Henry Knox and the Pluckemin military encampment, but also of a distinguished Dutch-American family deeply devoted to the Patriot cause.

The 5,000-plus square-foot restoration includes a 1,550 square-foot replica kitchen wing, constructed in 2007 on the site of the original kitchen footings found by archaeological excavation. The ADA-accessible wing provides a visitor reception area, rest rooms, kitchen and offices. In 2010, two permanent period room exhibits opened— the Vanderveer Parlor and the Knox Bedroom, supported through the generosity of the Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable and Educational Trust, and through a loan agreement with the Newark Museum. Furnishings on display include a Delaware Valley walnut William and Mary slant front desk (c. 1710-1735), a Delaware Valley gate leg table (c. 1780), gilt shell mirror, a Philadelphia Chippendale chair, and other period pieces. Furnishings loaned by the Newark Museum, include a Delaware Valley Queen Anne dressing table and a Queen Anne wing chair (c. 1740) once owned by New Jersey's distinguished Frelinghuysen family.

In 2011, the Friends unveiled a colonial kitchen hearth exhibit designed to show what the kitchen wing might have looked like at the time the Vanderveers lived there. The exhibit features unique carpentry, paint, furnishings and decorative accessories, along with a costumed mannequin depicting an enslaved girl known to have worked in the Vanderveer household. The centerpiece of the exhibit is a trompe l'oeil painting, by New Jersey artist Dan Mulligan, with realistic images of pots, cooking utensils, a fireplace screen and charred walls. Adjacent to the fireplace is a recently acquired cupboard displaying period cooking pieces. Also installed in 2011 was an upstairs lumber room, the equivalent of an attic storage and guest room. Informal furnishings, such as a bed, trunks, old wheelbarrows and spinning wheels include pieces meant-to-be-touched by visitors, especially children.

Upcoming plans include the creation of the Vanderveer-Knox History Center, dedicated to the preservation and sharing of local history. Supported by a generous contribution from a Somerset County resident, the Friends are furnishing a small 1813 parlor on the first floor of the house as a study center and library, with a small collection of books, documents and other research materials, along with appropriate period style furnishings.

Today, the Vanderveer house welcomes a growing number of visitors of all ages each month with educational and interpretive programs, such as house tours, family and children's events, hands-on living history activities, an annual Colonial Christmas celebration, Colonial Springfest, and other programs conducted in partnership with the Heritage Trail Association, other nearby Revolutionary War sites, Bedminster Township and Somerset County's Cultural and Heritage Commission.

The Friends lost a great ally when Mr. Sekel died in 2008, but John Seidel, who later wrote a dissertation about the archaeological project, remains an active partner. Working with Seidel, historical geographer Stewart Bruce, other historians, and students at Washington College, in Chestertown, MD., the Friends are using sophisticated mapping software to create a 3D visualization of the lost Pluckemin Cantonment in a series of digital animations interpreted and narrated by scholars. The depicts buildings (officers' quarters, armorers' shop, artificers' quarters, tin smith's shop, etc.) as well as the physical materials, tools and daily activities of life at the site.

The 21st-century digital exhibition complements the Friends' more traditional interpretive programs—authentic artifacts, beautiful period rooms, museum displays, art works, maps and printed materials. The virtual cantonment will be presented on-site at the Jacobus Vanderveer House Museum, posted on the museum's website and Facebook page and will be available for posting by other organizations. The story of America's first military academy, and its impact on the outcome of the war and the future of the nation will be there for all to see. Perhaps we'll share a part of Cliff Sekel's realization, which he described to the Star Ledger in 2002: "Whenever I come here, I can honestly picture in my mind the genius of these men. It never ceases to amaze me how little we know about them. We put them on pedestals and dehumanize them, but they are even more intriguing as mortals."

For more information about the Vanderveer House, upcoming events, and a sneek peek at how history meets high-tech in telling the story of the Pluckemin's long lost cantonment, visit the Friends' website.

Part of the Morristown National Historic Park, the formal walled garden, 200-foot wisteria-covered pergola, mountain laurel allee and North American perennials garden was designed by local landscape architect Clarence Fowler.

Even today, if you needed a natural hideout—a really good one—Jonathan’s Woods could work.

Paths of green, fields of gold!

The Jacobus Vanderveer house is the only surviving building associated with the Pluckemin encampment.

Dedicated to preserving the heritage and history of the railroads of New Jersey through the restoration, preservation, interpretation and operation of historic railroad equipment and artifacts, the museum is open Sundays, April thru October.