The Borough of High Bridge, located in the foothills of Hunterdon County, would on its face appear little different than any of the other many municipalities in New Jersey. However, the sign, “Settled in 1700”, which welcomes those who pass through this sleepy little town, implies a long abiding heritage: a story of the workers who helped shape the history and destiny of the United States.

The High Bridge saga began as early as 1664, when James, the Duke of York, conveyed the portion of land which eventually became New Jersey to Sir George Carteret and Lord John Berkley, friends and advisors to the King of England and the Court of Charles the second. Lord Berkley eventually sold his one half and hence divided the territory into West Jersey and East Jersey. In 1688, the resident proprietors created the West Jersey Council of Proprietors, and soon afterward, the West Jersey Society was formed consisting of English businessmen who retained title and right to their land.

English iron investors, William Allen, a Supreme Court justice and possibly the wealthiest man in Philadelphia; and Joseph Turner, a sea captain also active in politics; initially leased 3,000 acres from this West Jersey Society along the South Branch of the Raritan River in 1742 and founded what became known as Union Ironworks. Later, the Allen and Turner partnership purchased 10,849 acres that included parts of today’s Bethlehem Township, Clinton, Clinton Township, High Bridge and Lebanon Township. The area was predominately wilderness containing deposits of high quality iron ore, abundant timber to make charcoal, and plenty of water to power the Ironworks. After a few years of turmoil and conflict between Native Americans, squatters, and land speculators, Allen and Turner established two furnaces and two forges, each with two stacks, a trip hammer and a flatting hammer in the area of present day High Bridge. Allen’s enthusiastic statement of 1761 echoed, “Wood and water we can never want. Indeed we want nothing but good workmen.” Col. John Hackett, who had arrived to restore order at Union, became the first superintendent of the Iron Works, living adjacent to the operation in a modest residence, perhaps a farmer’s former tenant house, built in the early eighteenth century.

During the War for Independence, Robert Taylor, an Irish immigrant and former schoolteacher, became superintendent of the Ironworks and set to work casting cannonballs for the Revolutionary forces. Due to his support of the cause, Taylor was charged by General Washington’s Board of War with holding Loyalists John Penn, Royal Governor of Pennsylvania, and his attorney general, Benjamin Chew, under house arrest at the superintendent’s residence. The prisoners were, however, permitted to roam up to six miles from Union with an Italian fiddler at their disposal. Nevertheless, they named the house, Solitude.

In 1800, the New Jersey Supreme Court assigned a commission to divide the original ironworks properties between the Allen and Turner’s heirs, including Turner’s niece, Elizabeth Oswald, who was the wife of Benjamin Chew. Subsequently in 1803, Taylor purchased 366 Acres and founded the Taylor Iron and Steel Company, located at the site of High Bridge’s present-day Custom Alloy Corporation.

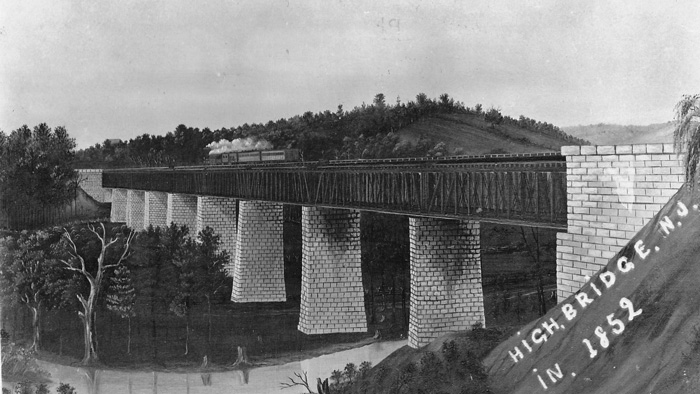

In the mid nineteenth century, the Central Jersey Railroad Company of New Jersey brought new life to Taylor’s ironworks, which by then depended on anthracite coal for fuel. To meet the demand for superior forgings, the company imported the newly invented, steam-operated Nasmyth hammer from England in 1854. The hammer currently resides at the National Museum of Industrial History in Bethlehem, PA.

High Bridge grew up a company town. At one time, nearly every citizen was associated with the Taylor Wharton Iron and Steel Company (TISCO), the longest continually operating iron and steel company in United States. If they did not work directly for TISCO or any of its derivatives directly, residents were part of the support system of the company employees who needed clothing, commerce, medicine, transportation and all the other accommodations of everyday life. High Bridgers watched vaudeville at the Rialto Theatre and lodged and dined at the American Hotel. They worshipped at Dutch reformed and Methodist Churches, or at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (whose cornerstone is from St. Brigid’s Abbey in County Cork, Ireland). These churches are still with us today. Sadly, the theatre and the hotel have passed into history demolished in the 1970s.

Working for TISCO sometimes meant long hours in unsafe or unsatisfactory conditions. Only through hard fought battles with the United Steelworkers of America (USA), were the workers granted some of the basic workforce protections and regulations that we take for granted today. My grandfather, William B. Honachefsky, was President of the local chapter of USA for many years, and I grew up with an acute awareness of High Bridge heritage. But, the memory of a once bustling farming community and factory town has faded. New generations of families arrive unaware of the importance of this special area, unfamiliar with an incredible story of commerce and industry, hard to fathom amidst today’s open spaces and quaint atmosphere. In 1999, I was one of thousands who signed a petition spurring the town fathers to create a permanent place for the history of High Bridge and beyond. Thus, the Union Forge Heritage Association (UFHA) created and operated the successful Solitude House Museum from 2002 to 2012.

Some of Solitude’s most famous visitors include George and Martha Washington, as well as General Lafayette, Colonel Charles Stewart, and Aaron Burr. Solitude House continued to host the superintendents of TISCO, including five generations of Taylors.

More of these historic structures and spaces were preserved and memorialized by UFHA in 2008 as the Taylor Steelworkers Historical Greenway, which abuts the former route of the Western Branch of the Central Jersey Railroad, now known as the Columbia Trail. Several miles north of High Bridge, the Columbia Trail passes over Ken Lockwood Gorge Bridge, built eighty feet above the gorge floor in 1930 to replace the original wooden trestle bridge, which was the site of a memorable 1886 train wreck.

The seven-mile Taylor Steelworkers Historical Greenway, which winds its way through High Bridge and beautiful surrounding countryside, is perfect for history buffs and wildlife watchers alike. Follow the Columbia Trail about a quarter mile in from its head near High Bridge Commons and look on your right for the Greenway trailhead gate. Head downhill through the woods, past the sound of rushing water over the Lake Solitude spillway towards the historic structures of the TISCO complex and headquarters. The TISCO Office Building dates to 1725, mostly likely the oldest office building in New Jersey, actually predating the incorporation of the Union Iron Works. Later renovations gave it the American Renaissance style you see today. The building has been vacant since the closing of Taylor Wharton in 1972. The gigantic concrete structure across the way is Grinding Shop E, a machine shop constructed in 1904 large enough to accommodate the rail cars that once crisscrossed the yard.

Walk left down the drive, then onto a hundred-year-old Carnegie truss bridge, restored by the UFHA and volunteers. After crossing the bridge, the trail proceeds north along the South Branch of the Raritan River along an easement provided by Custom Alloy. Stop at the ruins of the original bloomery, the earliest type of furnace capable of smelting wrought iron. The interpretive sign there explains that these last remaining stones, which have survived nearly three centuries, “represent the beginning of the thirteenth oldest continually operated company in world history.”

From the Union Forge remnants it’s a short walk to Solitude House, now standing eerily vacant with its associated state and nationally recognized historic structures: a former slave quarters, and a building that served as “bachelor quarters” during the Revolution, later a company store. Continue to Lake Solitude and Lake Solitude Dam, built in 1858 and later updated by master engineer Frank S. Tainter in 1909. The dam remains the last buttress dam in the state of New Jersey and a focal point for recreational activities, including trout fishing, canoeing, and picnicking.

From there, you can continue to the entrance of the Nassau Trail, which works its way to Springside Farm along a forested path enjoyed by hikers and bikers. Or you can walk, or drive, up the narrow Nassau Road past immaculate properties once owned by Taylor Steel executives, towards the remains of a grand old stone farmhouse first inhabited by Robert Taylor’s son, Archibald. The picturesque farmstead, which once produced fruits and vegetables for Taylor employees, and was later a working dairy farm, is now an expanse of open meadows dotted with the shells of a nineteenth century Wagon House and General Barn and Horse Barn, also recognized historic structures. Wind your way up through the fields towards the adjoining Springside Woods and choose among a lengthy series of loops through a pristine forest filled with natural wonder. Bald eagles are a familiar sight in the region, often easier to spot in winter when trees are bare of leaves. Check the trees along the trails; seasonal sightings include Brown Creeper, Eastern Phoebe, Ruby and Golden-crowned Kinglets, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Palm, Pine and Yellow-rumped Warblers and Yellow-throated Vireo. Look a little deeper into the woods for Hermit and Wood Thrushes, Veery, Ovenbird and Red-eyed and Blue-headed Vireos and Pileated Woodpecker. The most intrepid seekers of history can find their way to the Beaver Brook and follow it towards the remains of Lord Amesbury’s Furnace, built in 1752 as part of the original iron works.

By the mid twentieth century, the landscape near the site of the original Union Ironworks was not dissimilar to what it was during its yesteryear. Farm fields seemed to stretch on forever or at least until the next horizon, their boundaries delineated most often by narrow hedgerows and on occasion by wire fencing. In between crops lay pastureland for the grazing of robust dairy cows, ferociously guarded by free pastured herd bulls. If you crossed those fields, you had to be fleet of foot and able to leap a barbed wire fence in a single bound.

It is through this wonderful landscape that a little stream called Spruce Run wound its way southward out of the highlands of Schooley’s Mountain, the product of a multitude of shaded spring seeps discharging groundwater from the underlying bedrock below. By the time it passed under the two lane Route 30 (now Route 31) concrete roadway in Glen Gardner and flowed under Hurley’s bridge (now Van Syckle’s Road bridge) the gradient of the stream became more gradual, lazily wending its way under the shade of ancient sycamore trees. Here, its meandering pathway skirted the stone remnants of the historic, iron producing Union Furnace, part of Allen and Turner’s vast Union Ironworks in the early 1700s. Perched on a nearby bluff just above Spruce Run was the undisturbed 1747 grave of Nathaniel Irish, early manager of the Union Furnace whose peaceful interment was about to change dramatically. The construction of Spruce Run Reservoir altered this bucolic and historic landscape forever.

By 1781, the forests, which had once provided an acre each day for fuel, were depleted, and the Union Furnace shut down. Loyal to the English Crown, Allen and Turner fled during the American Revolution, and their young superintendent, Robert Taylor then shifted his attention to Union Forge along the South Branch of the Raritan River. In 1811, Hugh Exton purchased the “Union Farmstead”, part of the original Ironworks, from Allen’s heirs with payment in gold, surprising the settlement agent. Following a succession of ownership, Hunterdon County acquired ninety-two acres of the farm in 1980, a large part of today’s Union Furnace Preserve. Remnants of pig iron production are evident along the trail; also the site of a gristmill Exton built along the Spruce Run. The Hugh Exton home lies on the property of the New Jersey Water Supply Authority in Clinton Township, nestled against Spruce Run Reservoir with the cornerstone dated 1735. Rubble from the Union Furnace was removed during construction of the reservoir.

Despite his imprisonment at Solitude during the Revolution, Benjamin Chew thrived in early American society, providing legal council to the Founding Fathers during the writing of the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and cultivating friendships with Washington, Jefferson and Adams. For a summer retreat from Philadelphia, he and his wife, Elizabeth Oswald, came to the 1760 Turner house, the former residence for the Operations Superintendent for the Ironworks. In the 1830s, Chew’s descendants sold the home to Charles Carhart, who operated one of the most renowned farms in Hunterdon County history.

After construction of the reservoir, the house was acquired by the State of New Jersey in 1967, which later considered its demolition. Instead, the Union Forge Heritage Association negotiated a lease on the house and immediate property, and began plans to move their museum from Solitude House after extensive renovations to the historic Turner House were completed in 2012. Located at 117 Van Syckles Road in Hampton, the Solitude Heritage Museum houses UFHA’s extensive collection of artifacts and documentation from the Union Ironworks, along with a wide range of period furnishings and relevant exhibits. Open to the public, May through December on Sundays, the museum is also the site of many events during the year.

The writer is a lifetime resident of Clinton Township and has sat on the New Jersey 350th Commission, Clinton Township Historical Commission and Union Forge Heritage Association among others and his most recent publication “High Bridge” is available from Arcadiapublishing.com. For more information about UFHA, call 908/638-8650, 908/328-0725 or check the facebook.

Artisanal cheeses, wood fired breads, 100% grass-fed beef, whey fed pork, and suckled veal, 100% grass-fed ice cream, pasta made with Emmer wheat and our own free-range eggs, and pesto made with our own basil! Bread and cheesemaking workshops are held on the working farm as well as weekend tours and occasional concerts.

Delightful fantasies beyond words! Gold, Platinum & Silver Jewelry, Wildlife Photos, Crystal, Lighthouses. Perfume Bottles, Santas, Witches Balls, Oil Lamps, Paperweights, Chimes, Art Glass, Wishing Stars. Also offering jewelry and watch repair